Executive Vice President Susan Hinkson Talks Land Use, Zoning, and the Future of New York City

Susan Hinkson, RA, LLM, former Vice Chair and Commissioner of New York City’s Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA), recently joined the Capalino team as Executive Vice President in our Land Use, Housing and Real Estate Group.

Susan will apply her unique experience with the BSA, and her vast expertise in all matters related to New York City real estate, to our existing clients and will work to expand our service offering, including the addition of financial analysis to support BSA applications. To learn more about Susan read her bio here.

Below, Susan talks about her role at the BSA, the history of zoning and its influence in shaping our neighborhoods, and predictions for the future of New York City.

1. Last year New York City celebrated ‘100 Years of Zoning’, how did it all start?

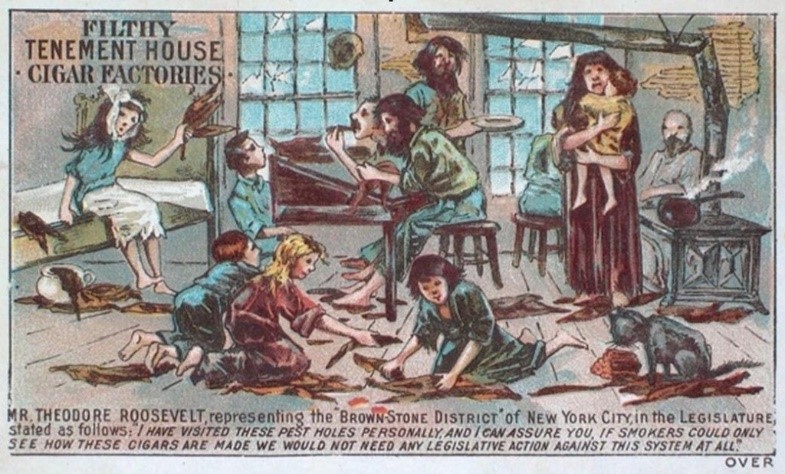

New York experienced great waves of migration during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, placing pressure on the City to accommodate and support significant commercial and residential growth. Competition for space was fierce, with residential and commercial activities co-mingled and intertwined. The American industrial revolution heralded a marked change from an otherwise rural agrarian society in the United States to an industrial urban-centric economy.

By the early 20th century, urban population growth soundly outstripped population growth in rural areas. Immigration and migration of people to urban centers to take advantage of the economic and social benefits of an expanding industrial base drove the population of cities like New York rapidly upward. Cities could not keep up with such rapid growth of a typically impoverished population seeking to make their fortunes in urban areas. Along with a booming economy came new technologies that enabled the building of taller, more robust buildings.

It was the combination of tall, densely built buildings alongside overcrowded and undersized tenement apartments housing both multiple family groups and manufacturing uses, without proper sanitation, light and air that sounded the clarion of change. Factories with noxious gases and poor ventilation were chock-a-block with tenement housing.

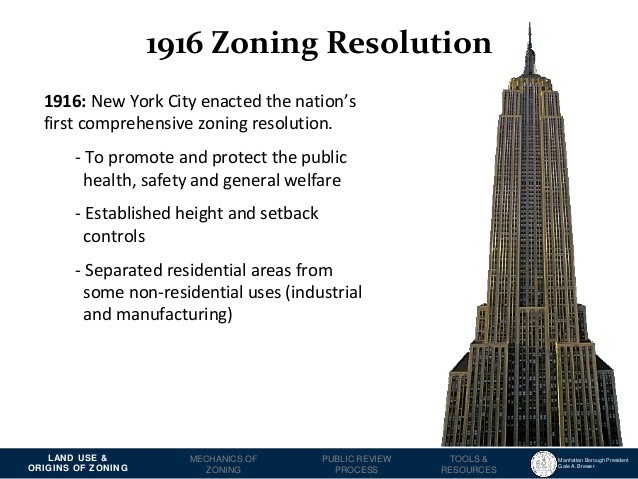

In response to the ever-growing pressure of substandard and oftentimes dangerous living conditions of 19th and early 20th century life, in July of 1916 New York City enacted the very first comprehensive set of laws that governed how a municipality’s uses and built forms intersect (or not) with each other to the benefit of its inhabitants. This law,now known as the Zoning Resolution, is a living document, meant over time to respond to the City’s changing landscape.

Even today, planners seek to prepare for the future of the city, trying to anticipate demographic shifts while allowing for industrial, commercial and retail development. This passage of laws that determined the use of land was a monumental step in government’s interaction with peoples’ lives, shaping the city’s environment of public and private space.

2. With zoning playing such an integral role in shaping neighborhood development and demographics, how does the city balance the need for growth with gentrification?

In a city as large and complex as New York, legislating the very physical substance of our collective lives can be, and often is, fraught with the understandable tensions created by the competing interests of multiple constituencies. The City is awash with movement as demographics ebb and flow through, and around, older neighborhoods such as Inwood in Manhattan or Ridgewood in Queens, while creating new popularized neighborhoods like BoCoCa (Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill & Carroll Gardens) in Brooklyn or SoLita (south of NoLita) in Manhattan. However, city planners must be continually aware of the changing nature of neighborhoods and weigh the economic impact on both real estate values and the human cost of possible displacement.

As a general matter, the City’s administrations, over the years, have made the preservation and creation of affordable housing a priority (some administrations more than others) involving various agencies, through a variety of initiatives, working with communities to identify areas of support for new development and to provide opportunities for preservation and retention of affordable housing. To that end, the Zoning Resolution provides opportunities and incentives to aid in the production and maintenance of affordable and accessible housing and to maintain economic diversity throughout the city.

The City’s Inclusionary Housing Program (HIP), provides for affordable housing to be built on the same site as market-rate housing or within the same community district, but must in any case be built within one-half mile of the market rate units being developed. As a result of several rezonings, the City has created designated areas, including contextual medium and high density neighborhoods that support the creation and maintenance of Inclusionary Housing.

Additionally, the City has implemented Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) in designated areas that affect both rezonings (public actions) and private developments. In these areas, developments of a certain size are required to devote a percentage of the building’s square footage permanently for affordable housing. These programs help to mitigate the effects of market forces that produce popular areas of the City that, over time, have become more expensive; pricing long-term residents as well as new lower and middle income residents out of the market.

3. As the former Vice Chair and Commissioner of the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA), what is the role of the BSA?

The Zoning Resolution was enacted as legislation that is generally applicable over the entire city. However, individual sites that were disproportionately or unduly restricted by land use regulations embodied in the Zoning Resolution required a relief valve to ensure that an individual’s property rights were not unconstitutionally impinged upon. Hence, the Board of Standards and Appeals (BSA) was born, primarily to protect the basic principle that an owner should be able to derive a reasonable return from his/her property.

The BSA interprets, and in some cases may vary or waive, provisions of the Zoning Resolution, the NYC Building Code, the NYC Fire Code, the New York State Multiple Dwelling Law and the Labor Law.Additionally, the BSA hears and decides applications from the Department of Buildings and the New York City Fire Department to modify or revoke certificates of occupancy.

4. Any predictions for the future? What will NYC look like 20-30 years from now?

Despite the sometimes volatile and contentious nature of the land use process, New York City continues to be at the forefront of dynamic city planning. The City attracts the best and the brightest in all fields, and that in no small measure includes architects and urban planners, engineers and visionaries.

That is not to say New York won’t have many challenges ahead in the coming years. A Pew research study published in February of 2014 indicated that the global population is swiftly aging, and that by 2050 the number of senior citizens will rise to 1.5 billion worldwide. In the US, the number of seniors will increase from 41 million today to 86 million in 2050. Additionally, the UN projects 66% of the world’s population will live in urban centers by 2050.

Taking these facts into account, our built environment will, by necessity, have to respond to a significant aging population with innovations in accessibility, siting and proximity to health care centers. Investment in infrastructure today will have a direct impact on how well goods and services are distributed to an aging population in and around the city of tomorrow.

Several symposiums have focused on the proliferation of drones and how buildings will be designed to incorporate drone deliveries or drone medical assistance, or simply how buildings must accommodate a drone’s path of flight. One can imagine the zoning issues that accompany drone activities.

Communications technologies will continue to influence our lives in significant ways that affect the way we live and work. Harkening back to the early part of the 20th century, when workers frequently lived in the same space where they worked, technology makes it possible to perform functions that heretofore were performed in an office setting, now can be performed in a live-work space, which in the future may become the norm rather than relegated to certain parts of the City. New emerging neighborhoods responding to the high cost of living may provide micro units for work/live sharing.

The future built environment will have to respond to a population as different from us as we were from our 19th century predecessors. Zoning affects where we live and work and how the physical environment is shaped and re-shaped to react to the changing texture of the City’s environmental fabric.

To learn more about Capalino’s Land Use, Housing + Real Estate services and how we can help you succeed in New York City, contact Susan at susan@nullcapalino.com or 212-616-5848.

Get The Latest From Capalino! Sign up for our free weekly newsletter for a roundup of top news and appointments from New York City and State government straight to your inbox every Friday. Click here to subscribe to Affairs+Appointments.